Page 80 - HIVMED_v21_i1.indb

P. 80

Page 7 of 8 Guideline

TABLE 3: Drug interactions with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Drug name Interaction Response

Aminoglycosides (e.g. amikacin and gentamicin used in drug-resistant TB) Possible additive nephrotoxicity Avoid concomitant TDF

TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; TB, tuberculosis.

PrEP offering: The time at which someone may be introduced to and invited to consider PrEP based on the anticipation/expectation of potential HIV exposure and lifestyle.

PrEP initiation: The point at which someone takes a bottle of pills home with the intention of using them effectively. Offering of PrEP and initiation can occur during a single

consultation if the client is knowledgeable and motivated to take PrEP.

Effective use: When drug levels in blood are high, PrEP is highly protective. For most populations, PrEP should be taken daily to prevent HIV. In heterosexual men and women,

daily dosing is recommended (see below). In men who have sex with men (MSM), on-demand PrEP can be used according to 2:1:1 strategy, whereby two pills of TDF-based PrEP

(i.e. a double dose) are taken 2–24 h before sex. If sex occurs, this should be followed up with one pill per day for 2 days after sex. The term ‘effective use’ is a preferred terminology

to ‘adherence’ to PrEP.

Persistence: Persistence refers to the consistency of taking PrEP over time. Persistence on PrEP is important for maintaining and increasing current reductions in new HIV

infections. Not all patients who initiate PrEP stay on it for long term, nor should they if their risk profile changes. ‘Persistence’ is the preferred terminology to ‘retention’ on PrEP.

Cycling on and off/seasons of use/episodic use: PrEP use and interruption, based on HIV risk behaviours including sex partners’ HIV status, number of sex partners, sexual activity

and condom use.

Client: Person who uses PrEP or is interested in using PrEP. The term ‘client’ is preferred rather than ‘patient’.

Potential exposure: Any potential sexual or other exposure to HIV. The term ‘potential exposure’ is preferred to ‘risk of HIV’.

On-demand PrEP: PrEP that is used at the time of a sexual event in which a potential HIV exposure could occur. This may overlap with post-exposure prophylaxis.

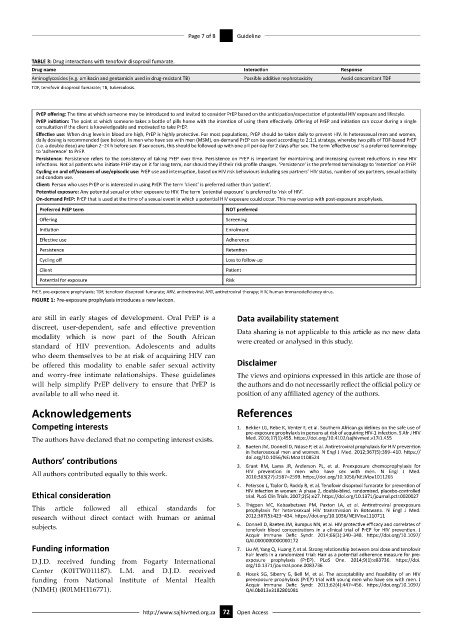

Preferred PrEP term NOT preferred

Offering Screening

Initiation Enrolment

Effective use Adherence

Persistence Retention

Cycling off Loss to follow-up

Client Patient

Potential for exposure Risk

PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; ARV, antiretroviral; ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

FIGURE 1: Pre-exposure prophylaxis introduces a new lexicon.

are still in early stages of development. Oral PrEP is a Data availability statement

discreet, user-dependent, safe and effective prevention Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data

modality which is now part of the South African were created or analysed in this study.

standard of HIV prevention. Adolescents and adults

who deem themselves to be at risk of acquiring HIV can

be offered this modality to enable safer sexual activity Disclaimer

and worry-free intimate relationships. These guidelines The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of

will help simplify PrEP delivery to ensure that PrEP is the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or

available to all who need it. position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

Acknowledgements References

Competing interests 1. Bekker LG, Rebe K, Venter F, et al. Southern African guidelines on the safe use of

pre-exposure prophylaxis in persons at risk of acquiring HIV-1 infection. S Afr J HIV

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists. Med. 2016;17(1):455. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhivmed.v17i1.455

2. Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention

in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. https://

Authors’ contributions doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1108524

3. Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for

All authors contributed equally to this work. HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med.

2010;363(27):2587–2599. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1011205

4. Peterson L, Taylor D, Roddy R, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for prevention of

Ethical consideration HIV infection in women: A phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled

trial. PLoS Clin Trials. 2007;2(5):e27. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pctr.0020027

5. Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure

This article followed all ethical standards for prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med.

research without direct contact with human or animal 2012;367(5):423–434. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1110711

subjects. 6. Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, et al. HIV protective efficacy and correlates of

tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention. J

Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(3):340–348. https://doi.org/10.1097/

QAI.0000000000000172

Funding information 7. Liu AY, Yang Q, Huang Y, et al. Strong relationship between oral dose and tenofovir

hair levels in a randomized trial: Hair as a potential adherence measure for pre-

D.J.D. received funding from Fogarty International exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e83736. https://doi.

org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083736

Center (K01TW011187). L.M. and D.J.D. received 8. Hosek SG, Siberry G, Bell M, et al. The acceptability and feasibility of an HIV

funding from National Institute of Mental Health preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) trial with young men who have sex with men. J

(NIMH) (R01MH116771). Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(4):447–456. https://doi.org/10.1097/

QAI.0b013e3182801081

http://www.sajhivmed.org.za 72 Open Access